Life cycle assessments: measuring impact to guide design decisions

A life cycle assessment (LCA) is a tool. They can be used as an external reporting tool, and they can be used as an internal design tool - to inform decision making.

The following is an overview and summary from our last event; Design & Impact.

The “classic” external reporting LCA

Generating an LCA that results in a publishable number is an intense process, and most likely the one you’re more familiar with seeing the output of. Check out TAKT’s climate footprint breakdowns for an example of human-readable product LCA data. The data should not be surprising at this point, just thorough and referenced. It can take a specialist consultancy months and £20,000 plus to go through the four stage iterative process:

Goal scope and definition - establishing the functional unit, relevant impact categories (there are 15 in total including Global Warming Potential and Acidification potential of land and water but currently there is no official metric for microplastics) and assessment type, e.g. cradle to gate.

Inventory compilation - gathering granular data for each aspect of the assessment. Often this will be sourced using primary methods, due to lack of available existing data.

Impact assessment - using (inventory values) x (emissions factors) to calculate impact quantitatively.

Interpretation - determining the significance of the data and providing recommendations.

As designers, we’re told we should be including them in development projects. But how and when? You’ve probably noticed that it’s impossible to do a robust, substantiated assessment of a concept before all decisions are finalised. Tony Elkington communicates this conundrum below.

Design Influence Ability vs Knowledge (Tony Elkington)

Fortunately, there are other types of life cycle assessment which sacrifice accuracy to align with design development speed and cost bandwidth. This is when LCAs are used as a design tool, either in-house or using specialist consultancies, such as 3Keel.

The design “tool” LCA

As a design tool, LCAs are used to guide decision making by using data to direct efforts into meaningful areas and to avoid inadvertently shifting burden into other areas. The earlier in the process that environmental impact can be considered, the more effective the design strategy can be. It is critical that these strategy decisions are informed, using methods such as LCAs.

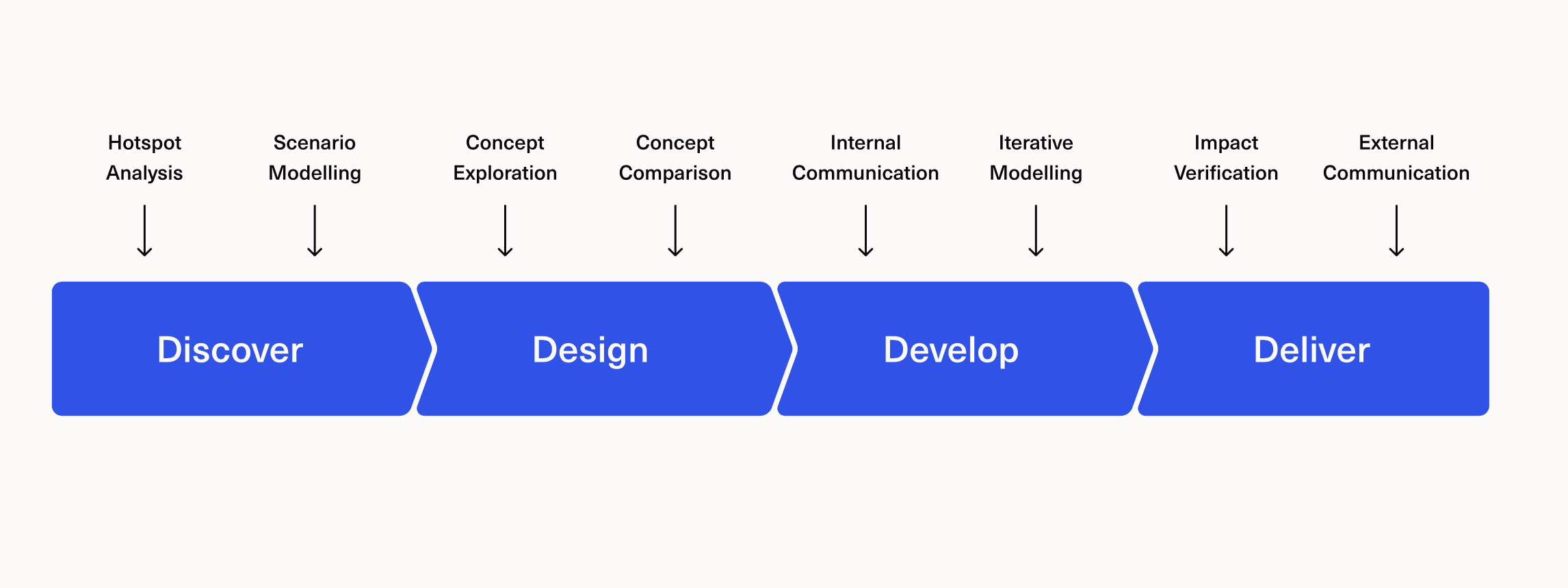

Across a product development process, there are lots of opportunities to use approximated data to better understand the impact trajectory. Tony Elkington outlines a framework which has 8 example approaches to measuring impact, with increasing rigor, throughout product development programmes.

Progressive LCA Applications (Tony Elkington)

The methods are versatile and may also be presented with alternative terminology:

“Product carbon footprint (PCF), “guidance tool”, “single product LCA” or “comparative LCA”.

Scenario modelling - uses “good enough” data to compare top level scenarios. For example, understanding the difference between design approaches that use a) alternative materials to directly substitute with higher impact conventional materials, b) light weighting methods to reduce quantity of existing materials, or c) implements renewable energy in its manufacturing processes.

Concept comparison - as more information is known about a design system, the life cycle data becomes relevant to consider alongside other requirements, for example ease of use, legislative compliance etc. This process highlights where the main trade-offs are, and enables design iterations to address critical feature compromises. A tip for this stage is to use proxy materials where data is unavailable for specific ones.

Impact verification - at this stage, the design is finalised and a preliminary life cycle analysis conducted using approximate secondary data. This is the decision point for whether to invest in a full LCA that can be published. If the results are indicatively favourable, the potential return on investment for sharing these are high - improved customer loyalty, established environmental credentials, opportunity for premium pricing.

Interpreting LCAs

Unfortunately even a full LCA doesn’t definitively answer the question: Which option is more sustainable?

Comparing products or concepts is always a trade-off. A design that performs well in one impact category often performs worse in another. Some methodologies attempt to combine all impacts into a single aggregated ‘sustainability score’ by applying weightings, which sounds great but oversimplifies a complex issue. Many impact categories, like water use and carbon emissions, aren't directly comparable, making their relative importance a subjective judgment.

In the end, identifying the “most sustainable” option depends on interpretation. The answer will vary depending on company priorities, the broader system context, and where change is most feasible. As designers, it’s helpful to treat LCAs as a decision making guide rather than a conclusive verdict. As Tony puts it, 'LCAs are often more of a dark art than an exact science' - which actually fits well with how designers already work. We're used to dealing with ambiguity, so the flexibility of LCAs can support creative decision-making, ultimately leading to more thoughtful and sustainable outcomes.

Conclusions

Both approaches to LCAs have their place and all LCAs should be viewed with curiosity, rather than absolute data, due to the subjectivity involved in determining what is “best”.

Useful Resources

IDE Mat app = free material database

2030 Calculator = free online LCA tool for use with simple products

CarbonSync = Paid startup LCA tool for designers/engineers

Written by Abby Hatch